Earthquakes

The 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile is the most powerful ever recorded. It lasted about 10 minutes and caused tsunamis that reached Hawaii, Japan, and even the Philippines. The New Madrid earthquakes (1811–1812) were so powerful they made the Mississippi River flow backward. Massive earthquakes can shift the Earth’s mass enough to change its rotation, slightly shortening the length of a day. The 2011 Japan quake shortened Earth’s day by about 1.8 microseconds. When an earthquake occurs under the ocean, it can shift the seafloor and displace massive amounts of water, causing a tsunami.

Floods

Floods happen more frequently than any other natural disaster worldwide — and they can happen almost anywhere, even deserts! A flash flood can occur within 6 hours or less of heavy rain — sometimes in less than 30 minutes — and can move with incredible speed and force. Just 6 inches of fast-moving water can knock a person down, and 2 feet can carry away a car! At the end of the last Ice Age, Glacial Lake Missoula in North America flooded with more water than all today’s rivers combined!

Landslides

Some landslides can move at speeds of over 160 km per hour — especially when mixed with water or ice. That’s as fast as a speeding car! Heavy rain is one of the most common causes of landslides. Just a few inches of rain over a short period can saturate the ground and send entire hillsides tumbling down. The 1963 Vajont Dam disaster in Italy happened when a massive landslide fell into the dam’s reservoir, causing a huge wave to overtop the dam and flood the valley below — killing around 2,000 people. Massive landslides under the ocean (called submarine landslides) can displace water and trigger tsunamis — sometimes without any earthquake involved.

Permafrost melting

Permafrost is ground that stays frozen for at least two years straight — but it can stay frozen for thousands of years! It can be made of soil, rocks, ice, and sometimes even ancient plant and animal remains. Permafrost preserves ancient viruses, bacteria, mammoths, and plants — basically freezing history in time. As the climate warms, permafrost is thawing and releasing greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide and methane — which could accelerate climate change. When permafrost melts, the ground sinks or shifts, causing buildings to crack or collapse. That’s why homes in permafrost zones are built on stilts or pilings.

Gas hydrates

Gas hydrates look like ice, but if you light them, they burn with a flame because they contain methane — a flammable gas trapped in water molecules. One cubic meter of gas hydrate can release up to 160 cubic meters of methane gas when melted. Gas hydrates form under high pressure and low temperatures, so they’re mostly found in deep ocean sediments and permafrost regions. Gas hydrates contain more energy than all other fossil fuels combined — in theory, they could power the planet for centuries. But mining them is extremely tricky and risky. When gas hydrates destabilize, they can cause underwater landslides, which in turn may trigger tsunamis. Bermuda’s Triangle theory: Methane hydrates suddenly decompose due to shifting temperatures or seafloor movement. Huge bubbles of methane gas rapidly rise to the ocean surface. The water becomes foamy and less dense — no longer able to support the weight of a ship. Ships could sink instantly, without warning — and leave no wreckage behind.

.png)

Offshore geotechnics

On land, gravity helps keep soil tests stable — but underwater, you’re dealing with buoyancy, water pressure, and soft, squishy seafloor sediments. Everything becomes way more complicated — and cool! We know more about the surface of Mars than the geology of the deep ocean. Offshore geotechnical engineers often explore uncharted ground, drilling or sampling in places no one has touched before. It’s part engineering, part deep-sea exploration. Offshore wind turbines might look like they’re just floating, but they’re anchored with monopiles or suction caissons up to 30+ meters deep!

Bio-geotechnics

Biogeotechnics often uses bacteria like Sporosarcina pasteurii to “grow” limestone in soil — making the ground stronger without cement or chemicals. This process is called microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) — basically letting microbes do the construction! Researchers are using biogeotechnics to create “living building materials” — like self-healing bricks and biocement — which could reduce reliance on carbon-heavy materials like concrete. Instead of digging, blasting, or pouring concrete, biogeotechnics gently tweaks the chemistry of the soil using natural processes. It’s like whispering to the Earth instead of shouting. Biogeotechnics is being considered for planetary colonization, like building roads or habitats on Mars using Martian soil and engineered bacteria. Who needs cement when you have space bugs?

Expansive soils

When expansive soils absorb water, they can swell enough to heave slabs and foundations, lifting entire structures by several inches! In dry conditions, expansive soils shrink and crack, causing buildings to settle unevenly or tilt. Sewer and water lines running through expansive soil often crack or dislocate as the ground shifts, leading to leaks and sinkholes. The behavior of expansive soils on Earth helps planetary scientists understand how Martian soils might respond to moisture and temperature changes.

Subsidence

It’s the gradual sinking or settling of the ground surface, often caused by natural or human activities. When underground mining removes materials like coal or salt, the ground above can collapse or sink over time. Uneven sinking can crack foundations, roads, and pipelines, leading to costly repairs. Pumping too much groundwater or oil from underground reservoirs can cause the land above to sink.

Sinkholes

Most sinkholes form in areas with limestone, gypsum, or salt beds — rocks that dissolve easily in water. These rocks get eaten away by acidic rainwater, creating underground caverns that collapse. The biggest urban sinkhole was in Guatemala City in 2010 — it was about 19.8 meters wide and 91.4 meters deep! Scientists have spotted possible sinkholes on the Moon and Mars, which could be entrances to underground caves — potential hideouts for future astronauts!

Underground storage reservoirs

Salt formations can be dissolved to create huge caverns — ideal for storing gases like natural gas or hydrogen safely underground. These caverns are tight and stable, perfect for long-term storage. Instead of storing energy in chemical batteries, underground energy storage uses natural features like caverns, aquifers, or depleted oil and gas fields to store energy — often in the form of compressed air, gas, or heat. Depleted oil and gas reservoirs can be repurposed as underground storage sites for natural gas or even hydrogen — turning old fossil fuel infrastructure into clean energy assets. You must be careful though — your stored hydrogen can be 'eaten' by underground bacteria!

Tsunamies

Unlike regular ocean waves, which are only a few meters apart, tsunami waves can have a wavelength of over 100 miles (160 km) — making them incredibly hard to detect in open water. Not all tsunamis are caused by earthquakes! Underwater landslides, volcanic eruptions, or even glacier collapses can displace water and generate massive waves. After the 1960 Chile earthquake, the resulting tsunami crossed the Pacific Ocean, hitting Hawaii, Japan, the Philippines, and even California. It took about 15 hours to reach Japan — and still caused major destruction.

Numerical modelling

Numerical modelling in geohazards is a powerful tool used to simulate and predict how natural hazards—like landslides, earthquakes, and floods—behave, helping engineers, scientists, and decision-makers reduce risk and design safer infrastructure. It involves using mathematical models and computer simulations to represent the physical processes behind geohazards, so we can: predict when and where a hazard might occur; understand the mechanics behind it; test mitigation measures; improve disaster preparedness. Virtual testing: Try different designs or scenarios without real-world risk. Disaster simulation: Understand “what if” situations (e.g., “What if this dam breaks?”).

And much more...

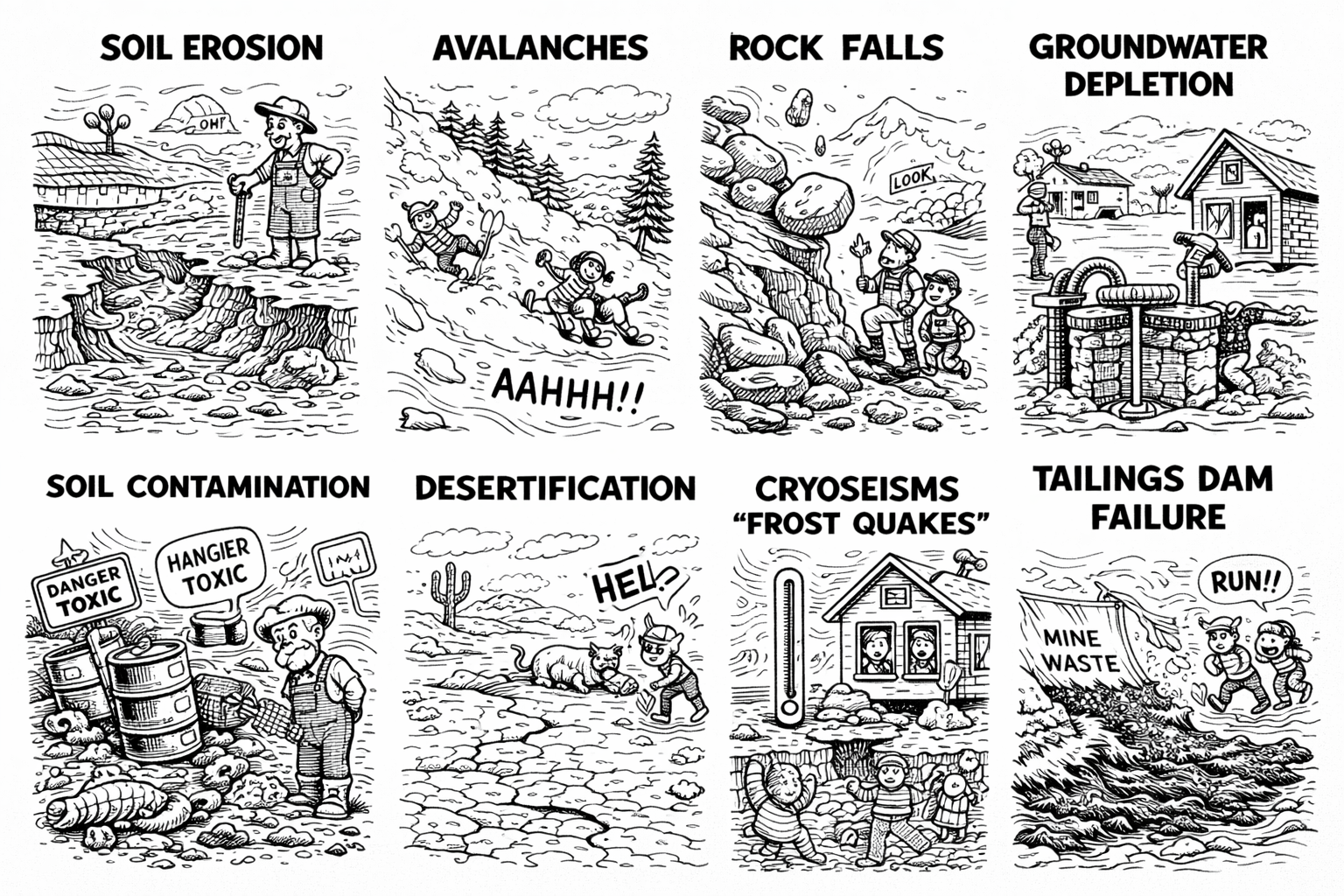

Volcanic eruptions, soil erosion, avalanches, rock falls, groundwater depletion, soil contamination, desertification, cryoseisms (frost quakes), tailings dam failures….

.png)